Fighting the Yellow Peril

Sinclair Jenkins, American Renaissance, August 1, 2019

In the 1932 film The Mask of Fu Manchu, the vile Dr. Fu Manchu (played by Boris Karloff) explains his goals for a Pan-Asian empire to an assembly of warlords: “[C]onquer and breed. Conquer the white man . . . and take his women!”

Even in 1932, when Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States had colonial holdings all throughout Asia, such blatant racial chauvinism was controversial. MGM, the studio that produced the film, fired director Charles Vidor after seeing an early draft. The studio worried that the censors would cut the film’s gratuitous scenes of torture and drug use. It was also afraid that the film would antagonize Chinese-Americans with dialog such as Dr. Van Berg (played by Jean Hersholt) skeptically asking, “A Chinamen beat me?” or Sir Dennis Smith (played by Lewis Stone) saying, “Do you suppose for a moment Fu Manchu doesn’t know that we have a beautiful white girl here with us?” For his part, Karloff’s Fu Manchu calls an Englishmen a “son of a white dog!” [1].

Many of the versions of The Mask of Fu Manchu available online have been edited to weaken the overtly racial message. You can find unedited versions if you know what to look for.

The idea that the Orient and the Occident will forever be at war, and that the East wants to defeat the West biologically, came from Sax Rohmer, the working-class Brummie who wrote The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu in 1913. Rohmer’s novel is widely credited with creating the literary pulp-fiction genre, the “Yellow Peril.”

Since the rise of the New Left of the 1960s, Asian scholars have earned praise and grant money by railing against the Anglo pulp fiction of yesteryear. Whole books and classes are dedicated to the “paranoia” of anti-Asian sentiment and the “pervasive” racism of Western society. These modern studies focus almost exclusively on attitudes towards Chinese immigration.

Ironically, the first country to ban Rohmer’s “Yellow Peril” yarns was Nazi Germany in 1936. Although Rohmer insisted that “my stories are not inimical to Nazi ideals,” the Third Reich banned Fu Manchu as both degenerate and the work of a suspected Jew.

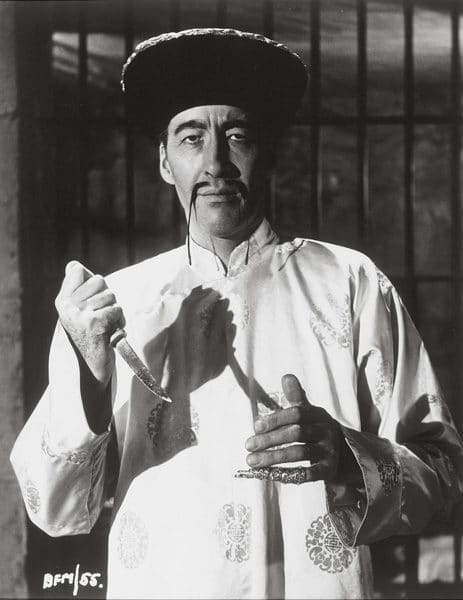

After the Second World War, there were independence movements in Asian colonies, but Yellow Peril stories continued to sell. In Britain, Hammer Film Productions got rich not only from Dracula and Frankenstein, but from a slew of villainous Chinese characters: Chung King in The Terror of the Tongs in 1961, and Fu Manchu himself in The Face of Fu Manchu in 1965, The Brides of Fu Manchu in 1966, The Vengeance of Fu Manchu in 1967, The Blood of Fu Manchu in 1968, and The Castle of Fu Manchu 1969.

Sir Christopher Lee as Fu Manchu in The Brides of Fu Manchu, 1966. (Credit Image: © ANGLO-AMALGAMATED/Entertainment Pictures/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Even earlier, an unabashedly imperialist and Yellow Peril comic series appeared. Created by the Belgian illustrator Edgar P. Jacobs, the Blake and Mortimer series began on September 26, 1946, with the publication of a short story called “The U Ray” in Tintin magazine. An expanded version become The Secret of the Swordfish in 1950, and the final graphic novel in the series was published in 1953 [2].

The stories were about Jacobs’s two principle characters: the Scottish scientist Philip Mortimer and his friend Captain Francis Blake of MI5. Blake and Mortimer, much like the Hammer films of the 1950s and 1960s, added futurist technology and modern sensibilities to otherwise deeply Victorian tales. Call it pop culture archaeofuturism or pulp fascism, but Blake and Mortimer reflected a populist European desire to maintain the order, stability, and glory of empire.

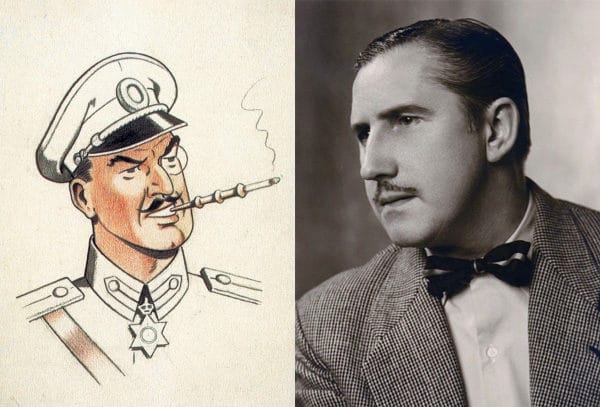

In all Blake and Mortimer stories, the main antagonist is the criminal adventurer Olrik, a mercenary colonel of Hungarian ancestry. With his thin, curled mustache and slick black hair, Olrik was based on the illustrator Jacobs. In The Secret of the Swordfish, Olrik is in the service of the Yellow Empire of Basam Damdu, an egomaniacal dictator headquartered in the Tibetan city of Lhasa. Like Fu Manchu, Emperor Damdu is hell-bent on reducing the white world to ashes. Damdu and his Yellow Empire is based on the Japanese Empire of the Second World War, and the East Asian Buddhist and Arab Muslim soldiers of Damdu’s army all dress in Imperial Japanese army uniforms.

Colonel Olrik and Edgar P. Jacobs

Many on the dissident Right praise Japan as an ethnostate and even defend its goals during the Second World War, but Jacobs and his generation saw things differently. For them, the Japanese army saw it as its divine mission to “lead the people of Asia out of slavery to the white man” [3]. This meant not only invading British Hong Kong, British Singapore, British Burma, French Indochina, the Dutch East Indies, and American Philippines, but also forcing white POWs to clean Chinese and Korean streets like coolies [4] to humble them before Asian crowds. Interning and raping white and Eurasian families on Java had the same purpose [5].

Emperor Dambu tries to outdo Genghis Khan, launching state-of-the-art rockets, jet fighters, and paratroopers. The Yellow Empire forces the British Empire and its American allies to their knees, and Emperor Damdu boasts that “Rome, the eternal city, is only a memory . . . . Paris, the city of light has been utterly crushed . . . . The proud metropolis of London has been turned to ash.”

All is not lost. Thanks to their pluck and determination and to Mortimer’s Swordfish jet fighter, British, American, and colonial Indian troops overthrow the Yellow Empire. Basam Damdu dies after a Gotterdammerung of his own making in Lhasa, while the resourceful Olrik flees to fight another day. In the stories that follow The Secret of the Swordfish, Olrik appears in British Egypt as a conman before ending up as a babbling wild man in the deserts of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.

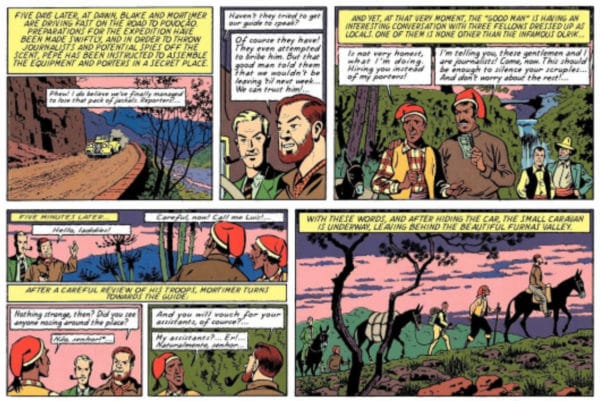

Click here for a full-size version.

Jacobs died at age 82 in 1987. Since then, Belgian writers and cartoonists have kept the Blake and Mortimer characters alive in comic books and on television. The imperialism of the Jacobs originals is still alive, too. Written by Yves Sente and drawn by Peter Van Dongen and Teun Berserik, The Valley of the Immortals, which was translated into English just last year, returns to the Yellow Peril themes of The Secret of the Swordfish.

Here, General Xi-Lee, a ruthless Chinese warlord based in the south, believes that he is the direct descendant Qin Shi Huang, the legendary first emperor of China. Xi-Lee wants to use this legacy and the recently discovered treasures of the first emperor to unite all of China under his rule. This would include taking over Hong Kong and Portuguese Macau. Blake and Mortimer, along with anti-communist Chinese (Xi-Lee has allied himself with Mao), defeat him from their base in Hong Kong, which is still British.

Other post-Jacobs graphic Black and Mortimer cartoon books are equally reactionary. 2010’s The Voronov Plot denounces Soviet communism and anyone who would resurrect Stalinism. 2013’s The Septimus Wave features Dr. Kim Ku-Dum, a former torturer from the Yellow Empire. Even in these new stories, the British Empire still rules the world and Asia is not to be trusted.

There is a straight line from Basam Damdu to Fu Manchu to Xi-Lee. All three see the world as a battleground between East and West, and all three want to destroy everything white and replace it with everything yellow. They are vicious and determined, but Blake and Mortimer always find a way to defeat them.

These stories remain popular and even critically celebrated. In 2004, Paris’s Palais de Chaillot hosted a huge exhibit of Blake and Mortimer. Between 1997 and 1998, French children gobbled up the Blake and Mortimer cartoon, and in 2014 it was announced that the beloved duo would finally get a new comic strip. English speakers in 2019 can enjoy old translations of the series and new editions thanks to British publisher Cinebook, all of which are available on Amazon and other online retailers.

Brussels, Belgium – Fresco of Blake and Mortimer. (Credit Image: © Degas Jean-Pierre/Hemis/ZUMAPRESS.com)

Although Blake and Mortimer are virtually unknown to Americans, they rank with Tintin and Asterix as the most popular comic-book heroes in Europe. Fans have bought more than 15 million copies, and the new incarnations sell in the hundreds of thousands.

The enduring popularity of Blake and Mortimer shows that readers in the West still want imperial adventures about strong white men. Blake and Mortimer are not the weaklings who live in London or Brussels today. They are like the hardy men who settled the American West, the Pioneer Column that planted the Union Jack in Rhodesia, and the British soldiers who fought two world wars to protect the Empire. French-speaking children love Blake and Mortimer; we should too. They are a reminder of our past and an inspiration for our future.

* * *

[1]: Tom Johnson, Censored Screams: The British Ban on Hollywood Horror in the Thirties (Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company, Inc.): p. 63-64.

[2]: Claude le Gallo, The World of Edgar P. Jacobs. In The Secret of the Swordfish, Part 3, Edgar P. Jacobs, Trans. Jerome Saincantin (Canterbury, Kent: Cinebook Ltd, 2013): 58.

[3]: Ian Mutsu, Introduction. In Edwin P. Hoyt, Warlord: Tojo Against the World (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001): xviii.

[4]: Hoyt, Warlord, 101-102.

[5]: Fred L. Borch, Military Trials of War Criminals in the Netherland East Indies, 1946-1949 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017): 19-35.